How the Amish Found Healing After the Nickel Mines Tragedy

By Nic Stoltzfus

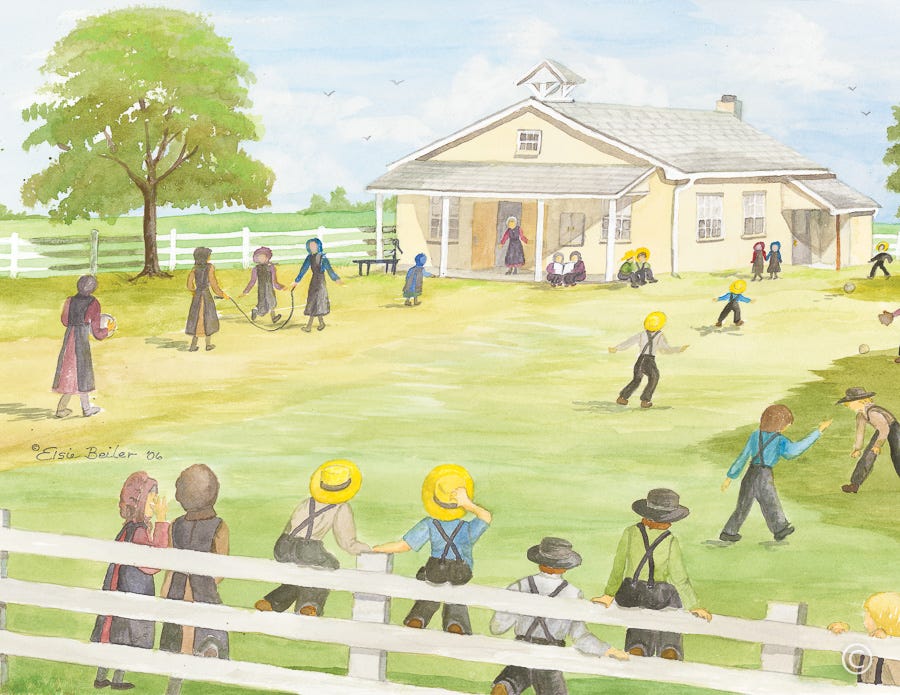

Two girls walk down White Oak Road, pass by the school’s white board fence, and walk up the gravel drive towards the yellow one-room schoolhouse. They are laughing, swapping stories about their weekend’s haps and mishaps. The fields surrounding the tree-shaded schoolhouse are bare, and the Amish farmers have already harvested their corn for the fall. It is a beautiful October morning—the sun overhead shines bright in the clear blue sky. The iron bell swings back and forth in the open belltower; its peals ring out, calling the children to class. School begins with a Bible reading from Acts 4. After, the children stand and recite the Lord’s Prayer in Pennsylvania Dutch.

Following the morning schoolwork, the students leave the schoolhouse for recess. The morning has started to warm up—perfect for a softball match. Their teacher, 20-year-old Emma Mae Zook, spends the break chatting with her mom, sister, and two sisters-in-law who are visiting for the day. Emma Mae is excited because her students will be singing for the visitors after recess. As she chats with her family, Emma keeps an eye on her students as they play. From the porch, Emma calls the students back to class.

~~~

It was another ordinary Monday morning for the students of West Nickel Mines, until a gunman entered the schoolhouse, shot ten girls, then killed himself. Five of the girls died: Naomi Rose Ebersol, Marian Stoltzfus Fisher, Lena Zook Miller, Mary Liz Miller, and Anna Mae Stoltzfus. Five of the girls survived: Barbara Fisher, Esther King, Rosanna King, Rachel Stoltzfus, and Sara Ann Stoltzfus. It was a shocking event for the Plain community, and one Amish man called it “Our 9/11.”

Immediately following the tragedy, those left behind tried to pick up pieces of their now fractured lives. One Amish grandfather who had lost his granddaughter that day consoled a group of shaken schoolboys standing outside the schoolhouse. Although overcome with grief at the loss of his granddaughter, he knew that the man who took her life had deep troubles in his heart. He said to the boys, “We must not think evil of this man.”

The gunman, a 32-year-old local man, left behind a wife and three young children. His wife, Marie, was heartbroken by what her husband did. In an open letter following the tragedy, she wrote, “Please know that our hearts have been broken by all that has happened. We are filled with sorrow for all of our Amish neighbors whom we have loved and continue to love…We know there are many hard days ahead for all the families who lost loved ones, and so we will continue to put our hope and trust in the God of all comfort, as we all seek to rebuild our lives."

Likewise, Chuck and Terri Roberts were shocked by their son’s violent actions. The afternoon of the shooting, Henry, one of their Amish neighbors, came to their house. Chuck came out to the porch to talk to Henry. His face was rubbed raw from wiping away the tears that had been streaming down his face all morning. Henry placed his hand on Chuck’s shoulder and shared with him words of forgiveness. Henry’s gentle words and actions brought comfort to the mourning father.

Terri Roberts, like her husband, was also overcome with grief and pain. That night as she laid in bed, Terri prayed to God and said, “God, this is the worst thing that I’ve ever heard of in my life. And my son is responsible for it? If there’s anything that you can use from this, you use it Lord, because I can’t imagine anything good coming from anything that happened on this day.”

At the burials following the shooting, the girls were peacefully laid to rest at a nearby Amish cemetery, buried in simple pine boxes. Marie attended one of the funerals. Marie’s husband was buried at the Georgetown Methodist Church cemetery, located only a few miles from the school. At 28 years old, she was a widow left to care for her three children, all younger than seven years old. At the funeral, over half of the 75 people in attendance were Amish; many of them were family members of the girls who were shot the week before.

The outpouring of support for the little community was enormous. Thousands of letters from all over the world poured into the local Bart Post Office, many of them containing donations or gifts. Some of the gifts were from people who had survived other tragic events. One such gift was the “Comfort Quilt,” originally stitched by schoolchildren after 9/11, that had traveled the country after various tragedies. The quilt was sent up to Nickel Mines from schoolchildren from Madison, Mississippi, who had survived Hurricane Katrina the year before.

One particularly poignant donation was an $11,000 check from the community of Picayune, Mississippi, that had also been devastated by Katrina. The community sent the donation because they felt a special connection to the Amish in Lancaster: after the storm, dozens of Amish carpenters had traveled south to repair roofs in the town of Picayune. This was their way to give back.

All told, over $4 million worth of donations came in. The Nickel Mines Accountability Committee was formed to manage the funds. The group, made up of seven Amish and two non-Amish members, allocated funds for the Amish families affected by the shooting. The shooter had left behind a widow with no source of income and three children who were now fatherless. Recognizing that the shooter’s family were also victims of the tragedy, the committee shared funds with Marie and her children.

The Amish of Nickel Mines found ways to reach out to others who had experienced loss, as well. On April 16th, 2007—A little over 6 months after the Nickel Mines shooting—the deadliest school shooting in U.S. history took place at Virginia Tech. A 23-year-old gunman killed 32 people and injured 29. Following the shooting, nearly thirty Amish from Nickel Mines took a bus down to the college to attend a Sunday memorial service. Along with them, in a plain wooden box, they brought a gift: the Comfort Quilt. At the service, the student body president thanked the Amish, saying, “The quilt is a sign, letting our students know that there are children around the world praying for us and for our friends that we have lost. Thank you for this very meaningful gift.” In reflecting about the event, one Amish grandfather whose granddaughter was killed during the shooting said, “It just felt good to talk to them. It’s amazing how God’s ways can help you heal.”

THE LONG ROAD TO HEALING

Fifteen years have passed since the Nickel Mines tragedy. Those affected by what happened on October 2nd, 2006, understand that healing is a long and challenging road. Even today, a decade and a half later, many struggle with forgiving the gunman for what he did. Every morning one makes the choice between the path of hostility and bitterness or the path of forgiveness and grace.

During a conversation with one of the parents who had children at the school, he talked about what forgiveness really is. He said that a strong foundation for children learning forgiveness is growing up in a home with two loving parents. Even if children have such a good start, they will not fully learn forgiveness in a year, two years, or even fifty years. Forgiveness is learning to accept whatever God puts in our hands, and this is a spiritual practice that takes a lifetime. The father shared a story that illustrated his point. “I was at a baptism service for some of our youth. The bishop told the youth that learning spiritual practices (like forgiveness) is like going to school. In 1st grade, you only knew a little. By 8th grade, you knew more. You will always continue to learn and keep growing in spiritual practices.”

In reflecting back on what he has learned over the past fifteen years, he said, “I learned more about the grace of God than I can put into words. Our God is so great and big, we can’t wrap our minds around how great God is. We have no power to forgive; it’s all through the grace of God.”

The Nickel Mines Accountability Committee—comprised mostly of Amish members—understood how forgiveness takes time, but it is possible through surrender to God. “The forgiveness extended by the Amish community to the Roberts family was noted around the world. The Amish did not wish such publicity for doing what Jesus taught and want to make sure that glory is given to God for that witness. Many from Nickel Mines have pointed out that forgiveness is a journey, that you need help from your community of faith and from God, and sometimes even from counselors, to make and hold on to a decision to not become a hostage to hostility. It is understood that hostility destroys community.”

Marie found healing by reaching out to God and her faith community. As a result, she was able to find freedom from the weight of her husband’s choices and the oppression of being labeled the “the shooter’s wife.” The year following her husband’s death, Marie remarried. In 2015, she and her husband Dan Monville adopted a child with special needs from South Africa. In a video telling their adoption story, Marie explains that the adoption has been a healing experience for the family, particularly her children. Marie said that “because of my kids’ loss of a father,” her children were able to have compassion for a child who has lost their parents. In an interview with Lancasteronline ten years following the tragedy, Marie said, “We all know pain and brokenness and loss. And if I hadn’t have gone through this, I wouldn’t have known that God truly can bring redemption and restoration over the worst circumstances. It doesn’t matter what you might have done or what might have been done to you, that’s not the end of the story.”

The Christmas following the tragedy—and for many years following—a bus of Amish carolers showed up in a yellow school bus to sing for Chuck and Terri Roberts. As the Amish reached out to the Roberts family, Chuck and Terri embraced the Amish in Nickel Mines, as well. They visited every family who lost a girl in the tragedy, and Terri had tea parties with the girls from the school and mothers and grandmothers from the area. In particular, Terri developed a special bond with Rosanna King, the youngest victim of the tragedy, who was most severely affected by what happened. Rosanna was unable to walk or talk and had severe seizures. For many years following the shooting, Terri drove to the King’s house every Thursday to spend the day with Rosanna. When Rosanna was younger, Terri rocked her in her arms and sang to her; she read to her from the Bible and from “Anne of Green Gables”; and she helped bathe her.

Reflecting on the Amish response to her son’s actions, Terri said, “They were willing to forgive, even on the first day. If they could forgive my son, how could I not forgive him? The Lord’s Prayer calls us to forgive, so I must forgive.” In another interview, also with Lancasteronline, ten years after the tragedy, she said, “I was so angry at what he had done. And yet, the realization that if I chose not to forgive him, I would have the same hole in my heart that he had…It is not automatic or without pain when we forgive. Forgiveness frees us to move forward, but it doesn’t take away all of the pain. It just helps us to know how to navigate the next step. And I think that’s what God has given me, has given the Amish community: the ability to take next steps in moving forward in order so that we can meet life and live life.”

BUILDING NEW HOPE

The week following the shooting, the boys rang the bell at the West Nickel Mines schoolhouse for the last time. Three days later, in the quiet before sunrise, a backhoe came in to dismantle the school. Dump trucks were loaded up with the disassembled building, carrying it away to a landfill. That morning a local Mennonite minister planted clover and grass seed over the barren ground, returning it to pasture. Later, five trees were planted in remembrance of the five girls.

Over the next few months, the community worked on completing a new school for the children. Local businesses donated material and labor, and one of the parents provided the land. The Nickel Mines school district overwhelmingly voted to name the school “New Hope.” According to one of the parents, the name represents “the hope that God is there and protecting us.” The first day of classes at New Hope school was on April 2nd, 2007, exactly six months after the tragedy.

~~~

On a cool Monday morning in early April, the New Hope school bell rings out, calling students to class for the first time. In groups of two or three, the children walk down the lane, past the newly planted maple trees, towards the red brick schoolhouse. Inside, Emma Mae Zook watches her students as they walk through the front door and take their seats. She leads the group in a Bible reading. Then, all the students stand and say in unison:

Our Father, who art in heaven,

hallowed be thy name;

thy kingdom come,

thy will be done

on earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread,

and forgive us our trespasses,

as we forgive those who trespass against us;

and lead us not into temptation,

but deliver us from evil.

For thine is the kingdom,

and the power, and the glory,

for ever and ever. Amen.

Donation Information

Many of the children and families still suffer from the tragedy at the West Nickel Mines school. Nickel Mines Accountability Committee (NMAC) still helps to pay for continued medical bills, doctor visits, and more. If you are interested in helping to support, please send your donations to NMAC, c/o Mark Beiler, 242 Country Lane, Christiana, PA 17509. Thank you and God bless.

More About Elsie Beiler, the Artist Behind “The Nickel Mines Series.”

The morning of October 2nd, Elsie Beiler heard the sirens and the helicopters from her home in Bart, less than two miles away from the West Nickel Mines school. Elsie turned on the television to the news, and she realized what had happened. She got in her car and drove over to her Amish neighbors, offering to take them down to the school. Many of Elsie’s neighbors were Amish, including Emma Mae Zook, the schoolteacher. Like many in the local community, Elsie was overcome with sadness about what happened. She thought back to those happier days when she drove past the school, and the children were out in the yard laughing and playing during recess. As a local artist who had recently picked back up painting in her late 50s, Elsie’s way of dealing with her grief was through her art. As she painted, “prayers and tears mixed with my paints as I worked with pencil and brush in hand. On my heart were the parents and families of these dear children, along with all the courageous people who responded in so many ways to their emergency.”

When she was finished, she decided to give a print of the painting to her neighbor, Emma Mae Zook. Later, at a meeting with the girls’ parents, Emma Mae shared the painting with them. The Ebersol family—who lost their daughter Naomi Rose in the tragedy—and Emma Mae decided that they wanted to give a print of the painting to the local Pennsylvania state police. This gift was presented to the police expressing their gratitude for all they did for the community following the tragedy. Today, Elsie Beiler’s painting “Happier Days” is displayed at the Troop J state police barracks in Lancaster County.

Over the next few years, Elsie did a series of five paintings in “The Nickel Mines Series.” In each painting, there are five birds in the sky, symbolizing the five girls who passed away. Along with the paintings, Elsie wrote some lines of comfort inspired by her pieces. She wrote the following words to go along “A New Day”, the third painting in the series:

Each day is new as the children gather at New Hope School in Nickel Mines. They are healing now. Life must go on. There are songs to sing, and prayers to pray. There are lessons to learn, new games to play.

I pray that each of us, along with the teacher and these precious children, will grow in COURAGE & FORGIVENESS, FRIENDSHIP & TRUST. May we find HOPE in GOD for each NEW DAY!

~~~

If you are interested in more artwork by Elsie Beiler, check out her Facebook page “Meadow Lane Designs” or contact her in these ways:

717-471-5594

~~~

Writer’s Bio:

Nic Stoltzfus is the Editorial Director of Plain Values magazine. From 2018 to 2020, he served as the caretaker of the Nicholas Stoltzfus Homestead in Reading, Pennsylvania. During this time, he wrote the book “In the Footsteps of My Stoltzfus Family: A Genealogy Memoir” (Masthof Press).