______________________________

THIS MONTH’S QUESTION:

What are your thoughts on the role education plays in a community?

______________________________

Emily: About twelve years ago, as we were pursuing an adoption we were on the phone with a potential birth mother. The conversation was going well when the question came up, will you be able to provide college and higher education for my child? A valid question, and one she had the right to ask—but a bit difficult for us to answer. The temptation was there to give vague reassurances, but these women deserve our complete respect and honesty, so we did our best to explain our reasons for not pursuing higher education. Did our answer help her make the decision to not choose us? We’ll never know, nor does it really matter.

This question is often asked, and I remember as a teen talking to my parents about it, wondering what the reasons are. As an adult now, it is so plain to me, and I’m grateful for the wisdom our forefathers had. They saw that a church and community function the best when we’re all on one level. There is no one on a higher tier who intimidates others and makes them feel like they are a lesser person. Almost every time in church, we hear about holding others higher than ourselves, and people having various degrees could definitely affect that.

Norman Rockwell’s painting Breaking Home Ties has always moved me. As a child, I would analyze it, trying to figure out what thoughts the father and the son are having. This painting depicts the threat of what higher education can do to our families and, ultimately, our communities. In the painting, the son, dressed in a brand-new suit and shiny shoes, looking fresh-faced and eager, is seated beside his father, obviously waiting for a bus to take him to the university. His suitcase and books are between his legs, and he’s holding a food parcel that his mother probably lovingly fixed. His father is a man of the land. He is no stranger to hard work by the looks of his hands, and he is not watching for the bus. He might be thinking that the boy is making something of himself, but I always felt he knew and grieved for what was being lost. Eventually, the cows will be sold, the Farmall M will languish in the shed, and he himself will move to town. Even the dog is feeling the change and has his head on the son’s knee, looking soulful, knowing his pal is leaving and will likely not return. I tend to be a bit fanciful, but I see this as what happens when they leave the farm for more education: they will not be back

Now lest anyone think that we don’t care about education and that as long as we know the basics we’re happy, let me clarify. The first Amish parochial school in this community opened its doors in the late 1940s in Wayne County, with Alma Kaufman as its teacher. Soon a few other schools followed. Although not legal according to the statutes of the State of Ohio, the schools stayed open because public opinion supported them. Then in 1972, attorney William B. Ball, representing the National Committee for Amish Religious Freedom, took a case involving parents in conflict with the State of Wisconsin to the United States Supreme Court. Mr. Ball, an expert in constitutional law and religion, presented our case, now known as Yoder v. Wisconsin, to the court. In a 7 to 0 vote delivered by Chief Justice Warren Burger, the high court held that the First and Fourteenth amendments prevented the states from compelling us to attend formal high school to the age of sixteen. A point of interest to me is that Chief Justice Burger and Associate Justice Harry Blackmun both attended the same rural one-room elementary school outside of Saint Paul, Minnesota.

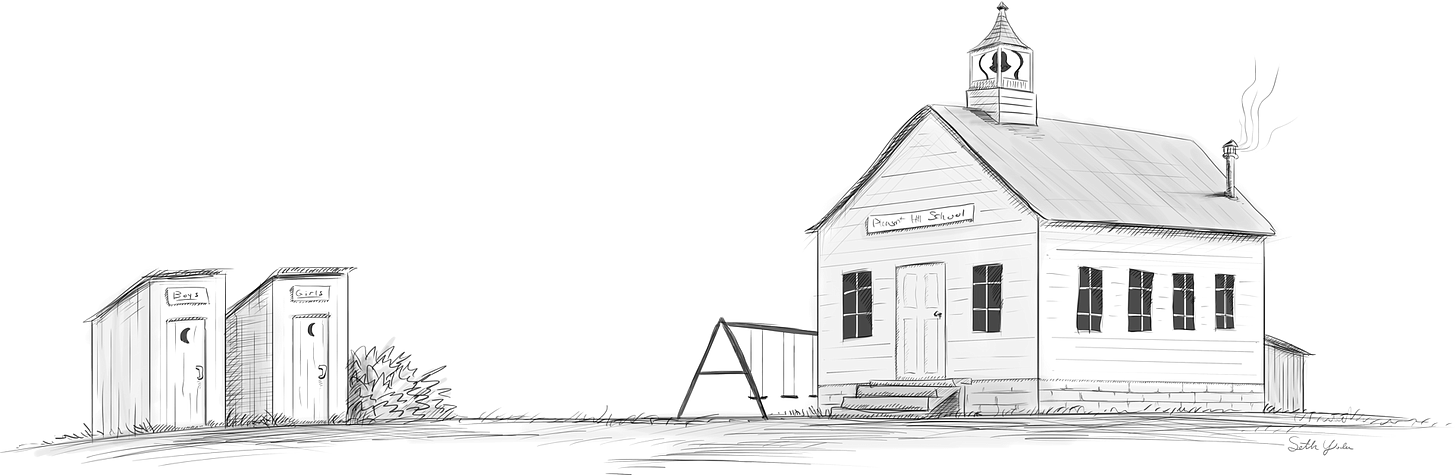

Now our schools became legal, and many more were built. I should add that in 1960, when our local rural one-room schools were closed in favor of central consolidation, many were purchased by the neighboring families and continued as parochial schools. I attended one of those schools.

Right now, there are approximately 70 schools in our community, with some children attending the small local public schools. Though we only go through eight grades and have a 160-day school year versus 180 like the public schools, most view it as the ideal window of opportunity to teach our children as much as possible. These eight years are formative academically and socially, and much is crammed in during this time. To be honest, there are some very lackluster schools where proper grammar is sadly lacking, and I’ve heard someone say that it’s the “dumbing down of the Amish.” But mostly, we have wonderfully dedicated teachers who put in all their efforts to create a safe and creative environment for their students. As a parent of children who have attended both public and parochial, I have concluded that while both have pros and cons, there is much we as parents can do to foster the thirst for learning.

I was fortunate to grow up in a home where I had all the tools I needed to keep on learning. Books, books, and more books! We had anything from Fire in the Zurich Hills by Elmo Stoll to Death in the Long Grass by Peter Hathaway Capstick. Childcraft: The How and Why Library, volumes 12 & 13, got me interested in history, and field guides gave us the resources we needed to identify things. With much of our continued learning coming from books and magazines, I like to think we remain more open-minded because we don’t just read things that we know we agree with. Education is a broad field, and we need a broad mind. Not as Ernest Hemingway said of his hometown in Illinois, “Where the lawns are broad and the minds are narrow.”

The adoption wasn’t meant to be, but it’s nice to think that if this birth mother could have lived in our community for a while, she would have rested easy, knowing her child would get a worthy education, just one that looks a bit different.

Daniel: Ask an Amishman in a straw hat about education, and he’ll likely glance at you from under a raised eyebrow. It’s not hard to figure out why. In opposition to the mainstream uber-education mind-set, the Amish deliberately choose 8 grades of basic schooling. Those 8 grades represent the education under my own straw hat, so my understanding of America’s advanced academic hierarchy is sketchy. I’m familiar, though, with how the Plain Community schools operate. After all, I’m one of us.

The differing models of education have been a source of serious contention in the past. A momentous ruling by the Supreme Court in 1975, Yoder vs. Iowa, exempted the Amish from state compulsory attendance beyond 8 grades, based on religious principles. A simple explanatory sentence such as that sidesteps the emotional trauma experienced by many Amish families where the father served jail time rather than comply with consolidation. Years ago, I read an excerpt from a professor that still rings in my head, a snippet having to do with the Amish school system: “They reject consolidated schools’ emphasis on science and technical competence because of its obsession with present findings that discredit the past and move the world in a progressive direction (F.H. Littell, 1969).” That’s pretty well it in a nutshell.

Since then, one-room schoolhouses have sprung up in every corner of Amishdom. The classrooms operate in a structured environment. Teachers themselves are 8th grade graduates, often young teenage girls several years removed from school, who now serve as role models for their students. They teach only the basic subjects, yet there’s an underlying but very real emphasis on community values and attitudes wrapped in cooperative activities, obedience, respect, diligence, kindness, and an appreciation for the natural world. Creativity is encouraged, not as much for self-advancement but for the good of all, to use God-given talents to further His kingdom.

Schoolhouses are geographically situated, more or less. Their localness to the students’ homes makes it handy for the children to walk or ride bikes, scooters, and pony carts. That in itself embraces neighborhood connectedness. In my neighborhood, Hickory Hollow School is tucked in a side hollow, just around the corner from our farm, a quarter mile away. Schoolchildren go by, morning and late afternoon, waving gaily. That, folks, makes my day. Community-wise, what more could you ask for? Their friendliness and cheer empower me to turn my day around. My waving back gives them a sense of belonging. After all, these very schoolchildren will, in the not-so-distant future, step into leadership roles as responsible adults in our society.

So much for classroom education. There’s much to be said for apprenticeship, where graduates in their early-to-mid-teens work shoulder to shoulder with dads, older brothers, and local tradesmen who act as mentors. Encounters in tradecraft and the work arena builds on the springboard of those 8 grades of schooling. As we well know, the school of life is always in session. Take nature; its workings unravel its mysteries if we but listen and learn. Life outside the classroom is an ongoing education, no matter what age or station. Pursuing a higher level of knowledge is there for whoever is willing to go after it. Come to think of it, one of America’s most beloved figures—Abraham Lincoln—self-educated himself to national and world prominence. His formal schooling amounted to less than one year. In his inimitable fashion, he used to say he was educated “by littles”—a little here, a little there. Despite his backwoods beginnings, Lincoln’s homespun wit and wisdom is being quoted yet today.

Personally, I’ve never once felt deprived by lack of education. People in my neighborhood and the larger community are living highly fulfilling lives on 8 grades of schooling. I see it first-hand. Having said that, the world we move in does require professionals. We rely on doctors and surgeons, lawyers, veterinarians, and other professions that demand hard-earned doctorates. While the Amish tap into uber-education in this way, our career choices are at the opposite end of the spectrum. At the same time, we recognize and applaud the expertise of these highly skilled and trained professionals.

So you see, although the Amish strongly promote education, we abbreviate and tailor it to fit within the framework of who we are and how we live. “…that we may lead a quiet and peaceable life in all godliness and honesty” (1 Timothy 2:2b).

_______________

Emily Hershberger with her husband and two children have an organic dairy near Mt Hope, Ohio. She enjoys farming, gardening, garage sales and a good book.

Daniel and Mae live on a 93-acre farm between Walnut Creek and Trail, Ohio. Five children, hay-making, and Black Angus cattle take up any spare time after work at Carlisle Printing. Questions and comments welcome: 330-893-6043.

Thank you for this thoughtful and thorough explanation... How appropriate it is that education "fit within the framework of who we are and how we live..." Education should serve--not dictate how we live.